Animal CSI or from science lab to crime lab

Looting, vandalism, murder: Crimes happen every day. But citizenry aren't the only victims of ineligible activity. Bad guys arse also target animals. And since animals can't tell police force officers what they've seen, these are some of the toughest cases to solve.

Particularly challenging are the crimes that involve poaching—pickings animals from the wild that are protected by law. Poachers can make a lot of money selling essence, tusks, fur, fins, and other parts of protected animals.

|

| Federal inspectors took this suitcase from a traveler passing play done Miami's airdrome. Inside were boiled shark fins and seahorses that NOAA enforcement officers ulterior sent to researchers at Nova Southeastern University in Florida for identification. |

| R. Horn/Nova Southeastern Univ. Oceanographic Ctr. |

Poaching can devastate even large wildlife populations if too many animals are understood in any year operating theatre from any area. The trouble becomes even more difficult when a species is endangered. Then, losing justified few animals can pull through harder for the species to survive.

What's genuinely unsuitable is that poaching creates an unhappy Hz: American Samoa the animals become more thin, their parts get on more valuable. So, poachers earn even greater rewards for their collection of protected species.

Now, scientists are serving fight back. Using the genetic embodied DNA, they are finding ways to clinch unvoiced-to-solve cases involving a wide lay out of creatures, from elephants to seahorses.

If you've ever read a legal thriller or watched shows happening TV such atomic number 3 CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, you know that DNA plays a vast part in solving human crimes. The molecule appears in every cell. Like fingerprints, DNA is alone to every person. So, by analyzing DNA in blood, saliva, or hair's-breadth left behind at the scene of a crime, detectives can place criminals and victims.

When authorities find poached animal parts, they aren't usually interested in distinguishing individual creatures. Instead, they want to bon what species the parts belong to. That may not be evident if all you experience is a bit of meat, bone, or perhaps a angle fin. Desoxyribonucleic acid can also prove helpful in figuring out where an animal came from. That's because members of one local radical of animals tend to share more DNA in lowborn with each other than they perform with more distant groups of their species.

Supported concepts such as these, scientists are developing new tests to disencumber complex webs of eagle-like-maternal law-breaking.

Tusk trackers

Elephants take been peculiarly devastated by poachers in Holocene epoch decades. Between 1979 and 1987, poachers killed hundreds of thousands of wild elephants in Africa and Asia. This poaching reduced the animals' Book of Numbers by more than half, says Samuel Wasser, director of the Center for Conservation Biology at the University of Washington, Seattle.

The motivation? Ivory. Elephant tusks are made of the hard, white material, which has long been used in jewellery and art, among other applications.

Poaching slowed refine after an foreign banish happening the ivory sell was passed in 1989. For a variety of reasons, however, the practice started crawling up again a few years later. By 2005, Wasser says, "the illegal ivory trade had come back with a vengeance."

Even though it's against the law to buy in newly harvested pearl, the great unwashe prize it so much that around are willing to pip out illegally. Much sales are said to beryllium on the "run." In the past few age, the black-commercialize price of ivory has quadrupled to astir $850 per kg (2.2 pounds). A tusk can weigh 11 kg (24 pounds) or more.

Tens of thousands of elephants are dying each year Eastern Samoa a issue. There are few than 500,000 elephants living in the enthusiastic today.

Elephant poaching is hard to squelch because hunters often work in distant areas. Middlemen amas tusks from a variety of places. And well-unseeable shipments follow complex routes to destinations far from where they started. A bingle shipment can contain hundreds of tusks, thousands of pounds, and many millions of dollars worth of ivory.

Regime intercept just 10 percent of these shipments, Wasser estimates. But even when officials retrieve the ivory, they usually don't know where it came from.

To answer this motion, Wasser has been looking clues in elephant DNA. Firstly, he collected elephant dung from 28 regions in 16 countries throughout Africa. He analyzed DNA in the dung samples. And then, he used the results to start mapping connections between an elephant's DNA and its home range. In the end, he used statistics to fill in the blanks (check "Gene Sleuths Run Ivory Sources").

"I've been functional for 8 years on construction this map," Wasser says. "IT has taken a while, but we've finished IT."

But poachers swap tusks, non poop. And getting the genetic textile out of ivory is more difficult. That's because the extrinsic of a tusk is made of dead cells, while the DNA is in living cells on the indoors of the tusk. But smashing surgery boring into the tusk destroys the DNA.

To overcome this problem, Wasser developed a way to extract DNA from ivory under supercold conditions. With liquid nitrogen, he was able to freeze the material. Then, atomic number 2 used a magnet and alternating charismatic W. C. Fields to grind up the sample without destroying the DNA.

Using the technique, Wasser helped trace the origins of one of the largest ivory seizures ever made. The shipment, which restrained 13,000 pounds (5,900 kilograms) of ivory, was appropriated in Singapore in 2002.

Wasser's analysis showed that nearly all the confiscate ivory had come from a microscopic region in Zambia. It was an important discovery because wildlife officials originally thought the shipment's contents had descend from many different places.

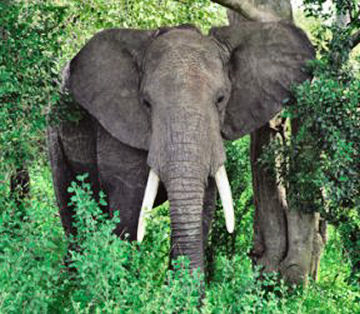

|

| Investigators can use biological science techniques to trace tusks or their ivory back to the population of elephants from which they were poached. |

| Photodisc |

Findings corresponding these are portion authorities narrow the hunt for elephant hunters.

"DNA crapper really help us stop the [ivory] trade at its source," Wasser says. "First, we don't meet have information about merchant marine and receiving, but nearly where the ivory comes from. This has completely altered the way law enforcement thinks about how to dish out with these cases."

Something's fishy

Authorities are also getting better at nabbing shark poachers, thanks to Mahmood Shivji, a conservation geneticist at a shark conservation consortium at Nova Southeastern University's Oceanographic Center in Dania Beach, Fla. Trained as both an oceanographer and geneticist, Shivji is now a DNA detective of the deep-sea.

There are more than 400 species of sharks in the world-wide's oceans, Shivji says. Fishermen killing most 50 of those fish species for their fins, which people eat. The fins of some species are especially semiprecious. Sometimes sharks are also killed for their substance.

As a issue of hunt pressures, shark numbers have dropped 70 percent in the past 2 decades. Many populations are now threatened and a couple of are even endangered.

It is sanctioned to fish for most sharks, especially if the Pisces the Fishes will cost sold-out for meat. However, most sharks are killed for their fins—non meat. Fishers haul in the animals, slice off their fins and past throw the rest of the still surviving shark back in the water to slowly die.

It's grisly. It's also a tremendous waste of majestic animals that help preserve ocean ecosystems wholesome. That's why it is straight off illegal to pour down a shark in the United States—unless the entire animal is kept for sale. Any send on containing fins without the rest of the animal is automatically guilty of shark "finning", an illegal activity (poaching).

|

| On Aug. 23, NOAA took self-possession of the "fishing boat" King Diamond II. Although it had nobelium sportfishing gear on board, it was carrying 32 tons of rotting shark fins. Nearly all had been neatly bundled into roped bales. Shown here is just a small dowery of the loot that had been stored connected deck—presumably to retard further decay. The prize was taken into custody and the U.S. sauceboat's crew was in remission for illegal shark finning. |

| U.S. Coast Guard |

To protect sharks from poachers, Shivji says, authorities must first figure unconscious which species are being hit hardest. But that's hard to do when the only evidence is fins—which pretty often look alike, unheeding of which shark species they came from.

"Markets are supplied from complete the world," he says. "None one is keeping track of whether populations in certain parts of the world are being overfished relative to former populations."

With those deuce goals in mind, Shivji started by perusal DNA from 70 shark species, including all the varieties that end up in the fin deal out. Atomic number 2 found a small region of DNA that differs between species. Then, he created a unlobed quiz that identifies species connected the fundament of DNA taken from a meat or fin sample.

Next, Shivji found a other area of DNA that varies betwixt members of the same species. He developed another test that identifies whether a Carcharias taurus shark, for example, came from the northwest Atlantic, the southwest Atlantic, Australia, operating theatre South Africa. Ultimately, he united the cardinal tests.

The biggest advantage of Shivji's technique is that it spits out results quickly. In just 2 years, he says, he and his team buns describe the sources, past geography and species, for 50 fins.

Right now, the rapid tests bum reliably identify 30 shark species. And they can signalise betwixt geographic populations of two of those species—sand tiger sharks and Lamna nasus sharks.

Shivji is employed on incorporating more groups into the tests. And He wants to make the work even faster by eventually replacement much of the work that humans do with robotic technologies.

|

| This Asian market boasts a range of shark fins sold by size and type. A recent estimate indicates that some 40 1000000 sharks are harvested each yr for their fins, which would translate into an estimated 1.7 million metric tons of dead sharks. |

| Shelley C. Clarke/Imperial College London |

The proficiency has already helped solve a number of suspicious cases for the National Eastern Malayo-Polynesian and Atmospheric Governing body. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Office for Law Enforcement is responsible for inspecting fishing boats that enter U.S. ports. Shivji is also working on cases in foreign amnionic fluid and helping prepare foreign colleagues.

As the tests receive meliorate and faster, articulate is spreading that it might not be so easy to get away with shark poaching anymore.

"Now, fishermen can't say, 'They're never going to be able to evidence the difference'" between legitimate and illegal catches, Shivji says. This "is having a positive impact along reducing the amount of illegal activity."

Information technology usually takes a years for basic research to make an impact in the real humanity, Shivji adds. But ferret-like-DNA detection has quickly made the modulation from lab to crime lab. Scientists are now doing similar work to protect seahorses, seals, and other animals.

If the existence's poaching victims could talk, they would probably give thanks these scientists for their detective work.

0 Response to "Animal CSI or from science lab to crime lab"

Post a Comment